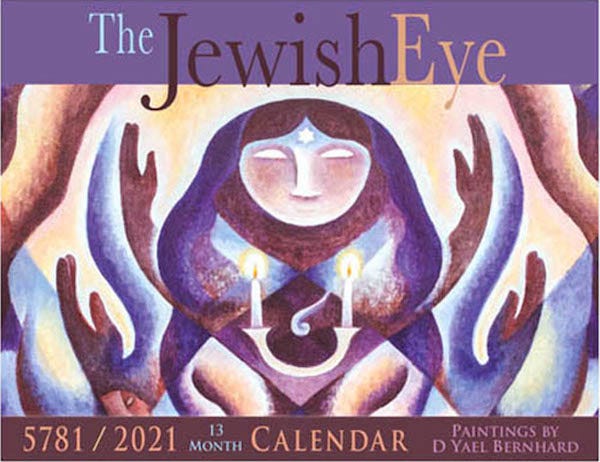

Image of the Week: Blue Shema

© D. Yael Bernhard

“I don’t believe in God – but what I do believe in, I call God.”

Thus reads my favorite bumper sticker, reminding us of the power of language, of a single word instilled in our culture – and the power of individual intention to overturn it.

One of the first Hebrew words I learned was kavanah – intention – often used to describe the intentions that breath life into a blessing or prayer. There is no prayer that is more central in Judaism than the Shema – or Sh'ma – the universal call to listen, hear, and understand that all concepts of God are one. Observant Jews recite the Sh'ma in every synagogue service, at every bar and bat mitzvah, upon waking and going to sleep, and ideally, at the moment of death.

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהוָה אֶחָֽד

Sh’ma Yisrael, Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai Echad

Hear O Israel, the Eternal is our God, the Eternal is One!

This universal declaration of Oneness seems clear enough, yet the intentions behind it have evolved over three millennia, reflecting the era in which it is recited. When the Sh’ma first appeared in Deuteronomy, the emphasis was on “only one God,” abolishing the belief that a graven image, sculpted idolor force of nature possesses the power of a deity. To the Kabbalists of the Middle Ages, the Sh'ma signified the unification of masculine and feminine, and of the six directions of space. In our present-day age of science and social justice, Oneness speaks to the imperative to embrace diversity and transcend boundaries. The secret of the Sh'ma is that it changes along with tradition, giving voice to our shared sensibilities.

At the same time, individual perceptions of God dwell within like a secret treasure. What is hidden there, nobody knows. In Judaism, your personal belief – or choice not to believe – in God is your secret. Thus many people cover their eyes while reciting the Sh'ma, and even lift their prayer shawl over their head. We gather the fringes – half matter, half spirit – of our prayer shawl into one unified bundle. We go into a private space, and surrounded by people, we are alone with our concept of the Eternal.

This dichotomy of individuality within a collective is beautifully embodied in Judaism, and is a theme that recurs in my art. In Blue Shema, the individual emerges from a collective of mosaic-like painted squares filled with gradients of changing color, many with blurred boundaries. The parts that make up this whole are shifting and transforming, pulsing with life.

The woman, of course, is an interpretive self-portrait, pixelated by the many influences that forge my own kavanah in reciting the Sh’ma. I am a collective within an individual, and an individual within a collective. This painting is also influenced by early 20th century art, as I was taking a college course on that period of art history at the time. The colors of the Fauves, the fractionated space of the Cubists, and the emotive energy of the Expressionists all played a part – as well as my love of mosaics, which date back to the Roman courts and palaces that ruled over ancient Judea, when the great Rabbi Akiba ben Joseph was famously martyred with the Sh’ma upon his lips.

As for my personal belief in God – nobody treads there but me, thank goodness. Like a crooked tree, it’s a flawed but deeply rooted faith, a work in progress that I wrestle with every day. Like the author of that bumper sticker, I’m not crazy about this German-derived word that somehow became endemic in our culture. I could write a whole post about the alternative names of God – but the point of the word is to point beyond itself to something wordless.

Personally, I think a painting can do just as well – if not better.

Blue Shema is the image for April in in my calendar, The Jewish Eye 5781/2021 Calendar of Art.

The Jewish Eye is available in my webstore ($18 including shipping) or on Amazon ($18 prime).

A good week to all!

D Yael Bernhard