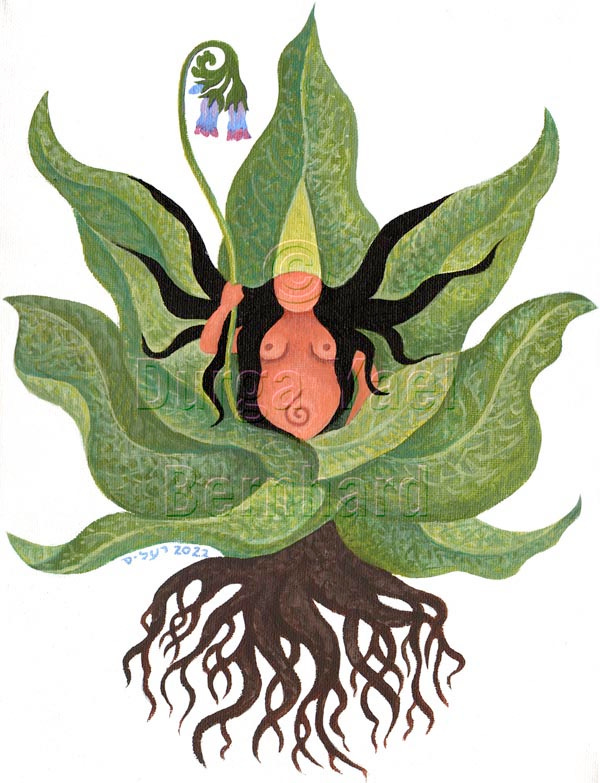

Image of the Week: Comfrey Goddess

© Durga Yael Bernhard

This illustration was recently commissioned by herbalist Susun Weed for her forthcoming Comfrey Conference, to take place from May 9-15. This online event offers a variety of teachings from numerous presenters, but has a single purpose: to exonerate the name and restore trust in the use of this plant long prized for its marvelous healing properties.

Comfrey, otherwise known as Symphytum officinale (the wild plant) or Symphytum uplandica (the cultivated variety), has long been prized by herbalists for its tissue-regenerating properties, as well as its minerals, proteins, and many vitamins. Yet comfrey has been maligned for its alleged liver toxin, a case of botched science if ever there was one. Here is an example from a well-known website – enough to scare your socks off and make you miss out on one of nature's great healing gifts.

In one of her books, Wise Woman Herbal for the Menopausal Years, Susun dispenses with this smear campaign in two sentences: only the wild plant contains liver-congesting pyrrolizidine alkaloids, and this plant is rarely, if ever, found in the United States. The leaves of the cultivated plant do not contain harmful compounds. Four decades of research back this up, with not a single incidence of liver toxicity. This doesn’t surprise me, for most plants in their natural form have far less toxicity or side effects than drugs. There are, of course, exceptions, just as there are a few drugs that don’t have side effects.

To this I would add my own experience: I've been using both comfrey root and leaf for decades, including in pregnancy, with no ill effects. On the contrary, I feel I owe much gratitude to this wonderful plant, which healed my menstrual difficulties in my twenties; helped me exceed expectations in recovering from rotator cuff surgery in my thirties; enabled me to bounce back quickly from childbirth in my forties; and has been instrumental in maintaining my connective tissue as I age. Comfrey leaves are a regular part of the daily herbal infusion I've been drinking for almost forty years. With its mucilaginous properties, the root is more often used as a poultice and applied externally.

Comfrey plants contain alantoin, a substance that helps generate new tissue growth and maintain elasticity. The large, abundant leaves – some as long as 18" – have the unique characteristic of anastomosis – diverging branches of veins that come back together and join with themselves again. Anastomosis is found in mushroom mycelium, but among plants it's rare. Comfrey not only knits new tissue, but knits with itself in a living, growing mesh of expansion and reconnection.

I’ve illustrated two of Susun’s books, but only in black and white; this was a welcome opportunity to bring her vision alive in color. Susun is fond of fairies and goddesses, and envisions plants as healing allies that rise from the earth. Personified thus, comfrey becomes a powerful she-creature, promising to strengthen and support our bodies on the cellular level. With her long black hair, this little goddess resembles Susun herself – although I'm not sure she'd agree. Regardless, I’m honored to collaborate with an herbalist of such broad knowledge and strong vision, and to contribute to her special event.

Want to learn more about the amazing comfrey plant? You can do so this coming week by attending the Comfrey Conference. It's free!

A good week to all!