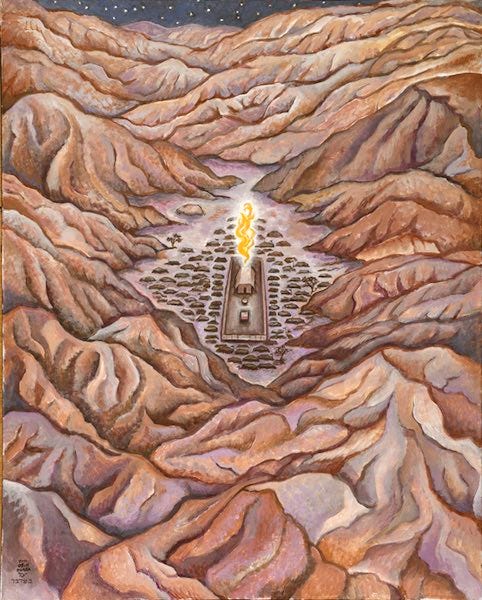

Image of the Week: In the Wilderness

© D. Yael Bernhard

This painting envisions a passage from the Torah (Hebrew Bible, or "Old Testament") that was read this past week in Jewish communities all over the world. It's the first passage in the "Book of Numbers," as the title translates from Greek, or Bamidbar (במדבר) in Hebrew, which means "In the Wilderness." That's quite a different meaning! How do numbers relate to wilderness?

The answer is simple: what happened in the wilderness was – well, counting. Following their liberation from slavery under the leadership of Moses, the Israelites had fled Egypt and now found themselves wandering in the wilderness of the Sinai desert, struggling to survive and striving to form themselves into a free and self-governing society. Taking a census of the people – men of fighting age, women of childbearing age – was a vital first step in this process. Each family belonged to a tribe descended from the sons of Jacob. These tribes were arranged around a central sanctuary tent to form an organized desert encampment. Known as the Tent of Meeting or Mishcan, this was no ordinary tent – it was nothing less than a traveling temple, with an altar and sacred objects housed within, including the spirit of the Eternal that sent up a plume of fire at night to light the encampment, and a pillar of cloud by day that guided the "children" of Israel on their long journey through the wilderness.

Nor was this an ordinary wilderness. The Sinai desert is a harsh and craggy landscape, seemingly inhospitable to human life. Such terrain defies ownership, forming a neutral ground in which the fledgling nation could form itself according to principles and beliefs, rather than property. The Sinai was an empty cauldron in which an unprecedented alchemy took place: the forging of a new belief in one transcendent God – a God that took interest in the people as a parent tends to children, shaping them with tender care and tough love.

Furthermore, the three-letter root of this word for "wilderness" roughly translates to mean "substance," – a nuance untranslatable into English but which approaches the Hindu concept of "maya" – which roughly means "that which exists, but is constantly changing and thus is spiritually unreal." Thus bamidbar and maya both connote the substance of material existence as something that cannot ultimately be owned, fixed, or grasped – but which we, in our human condition, must travel through.

Wow! This was all new to me when I did this painting ten years ago. Coming from a background in Eastern religion, I was delighted to find a bridge between those belief systems and Judaism, the tradition I inherited and finally embraced in my mid-forties. For my 50th birthday I took on this painting as part of my adult bat mitzvah, which took place in May 2011. I learned, and sang, the passage of Torah in Hebrew, studying the traditional cantillations that were assigned to each word approximately one thousand years ago. I delved into the historical significance of the passage, and searched for its hidden meaning.

Now a decade later, I find myself revisiting the passage through a new lens: that of American history. I'm presently reading the biography of Alexander Hamilton, written by Ron Chernow – a thick book that chronicles the life and work of the founding father who is perhaps most responsible for forging the language and precepts of our Constitution, and who established the United States treasury.

Hamilton was a deeply principled man who was incredibly adept with numbers; and his wife Eliza was a devoted and educated Christian. Together they raised eight children. A strong advocate for centralized government, Hamilton worked tirelessly to craft a replacement for the ill-conceived Articles of Confederation. He was gifted with fluency in both commerce and law, as well as writing and research, which he undertook at a level far beyond his years. He contributed over fifty essays to the Federalist Papers which encapsulate some of our present-day government's highest ideals. Hamilton was a realist who had studied history, and who understood the resources needed to form a cohesive nation.

How does Hamilton's unstoppable vision of government relate to the ancient concept of a universal, invisible Creator? As the pillar of fire pushes back the dark wilderness night, so too does the light of a just and moral government push back the darkness of ignorance and greed. Can the colonies that formed into states around a central government be compared to the twelve tribes of Jacob that formed themselves around the traveling Mishcan?

Thinking in visual terms, I saw the Sinai mountains as finger-like projections encircling the encampment, which in turn surround the Mishcan. Out of this landscape of random shapes, I tried to create an interplay of organic and structured forms. The wilderness surrounds and dwarfs this incipient society – but at its center, the society is illuminated by a spirit even greater than nature – that of Creation itself. The concentric circles of nucleus, protoplasm and cell walls also come to mind.

Did Alexander Hamilton ponder such things in conceiving a new nation? Certainly he looked over his shoulder at ancient history, religion and philosophy, even alluding to specific texts in his arguments. Whether or not he drew inspiration directly from the Bible, I do not know – I'm only halfway through the book as I write these words. But Hamilton's unceasing efforts to forge a union of federal and state power certainly bears the mark of the ancient metaphors of Bamidbar – for certainly ours was a land of uncharted territory in the early years of the United States of America – an intellectual wilderness that only a gritty realist like Hamilton could navigate. Numbers played a role in this fledgling society, but they could not, and should not, be the shining light at its center.

A good week to all!

D Yael Bernhard