Image of the Week: Seth the Slave Boy

© Durga Yael Bernhard

Here are several illustrations I did for an elementary school textbook chapter on American history. The story is about a child named Seth, maybe seven years old – a slave boy on a rice plantation in South Carolina, before the Civil War. As a "leveled reader," the story is also meant to teach vocabulary.

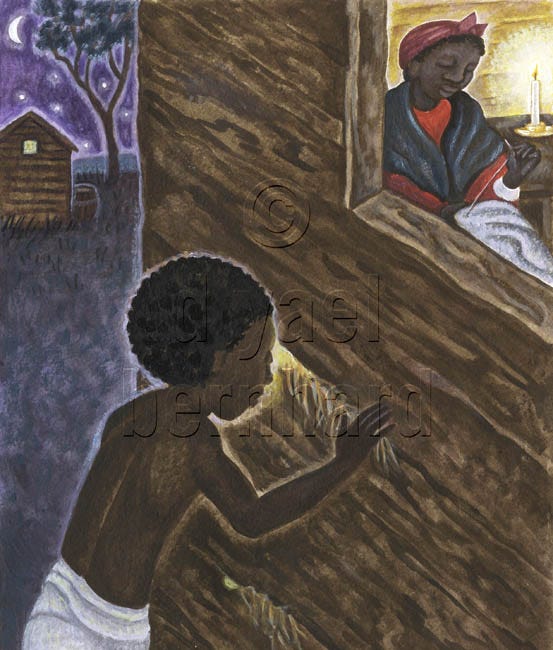

How do you show slavery to a third or fourth-grader? How do you teach the dark side of our nation's history? In a word, selectively. The story amplifies those aspects of life that are relatively normal for Seth and the other slave children. These kids love to play hide and seek, and get into mischief just like all children. In the above image, young Seth has been out playing with his friends too long and completely missed supper; now he wonders how he can sneak into the shanty without his mama seeing him, so as to avoid a scolding. In the image below, Seth has fallen asleep in his hiding place, and wakes up under a rice sack, startled to find the moon has already risen. These childish antics are normal and familiar. That's a good thing.

But normal stops about there for a child of slavery, no matter where he's shackled, no matter what century, which country, what master owns him. There, too, stops the job of the illustrator, as only a hint of suffering is allowed in the art. A whip may be raised over the back of a slave, but only before it strikes. Better not to show the slave's face, either. Better for young readers – for now.

Do I wish I could show more? Yes and no. Even the idea of suffering can be a lot for a child to absorb. A young mind is a tender thing. Though positive or neutral images don't show the whole picture, they do engender sympathy and encourage universal relating. Children can get a wider view later, as their minds broaden and they learn to think about what it means to be human.

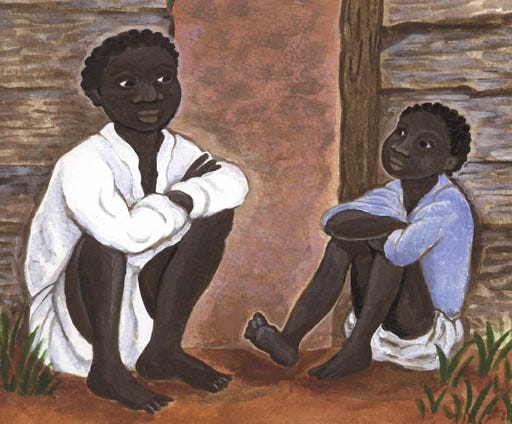

For now, the story turns to what Seth himself is thinking about: his future. In the scene below, he consults his older brother, who has seen life on another plantation. "On a tobacco plantation," the elder boy explains, "You work from sunup to sundown. You get no time off." Yet farming rice is no picnic either, as the slaves must work in swampy waters, full of snakes and insects that cause swamp fever.

Despite these harsh realities, the story allows the two brothers their hopes and dreams, their curiosity and fear. I enjoyed painting them, sitting side by side in the early evening, maybe watching a sunset. I should have added a cricket! As I worked, I thought about boys I've known, including my own son, and tried to bring their attributes into these characters.

Overall, this was one of my more challenging and satisfying educational assignments. My gratitude to my agent, Ronnie Herman, for obtaining it – and to the author and editors, with whom I never had direct contact. They did a good job. I hope this story helped build a foundation of understanding and compassion in young readers. Every stone in that foundation counts.

A good week to all!

D Yael Bernhard