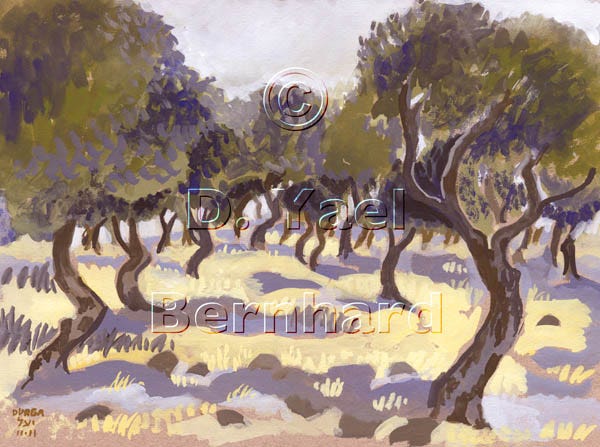

Image of the Week: Study of Olive Grove, Kaditah

© D. Yael Bernhard

It's easy to think of olive trees as people. Lithe and curvaceous in their youth, gnarly and sculpted in the fullness of maturity, they have as much individual character as any human. As olive trees age, their bark wrinkles and folds like wizened, leathery skin; the roots bulge like bony, weathered feet; the branches twist like dancers' arms, frozen in the most expressive gestures. Yet they're not frozen, and the trees continue to grow, slow as the wheel of time. Olives can live for well over a millennia, and sometimes twice that. As long as the roots do not burn or freeze, an olive tree can regenerate new trunks and branches – making it a potent symbol of renewed life. It's no accident that an olive tree was chosen for the cross of Jesus – despite its lack of wood that is long enough or straight enough to build a cross taller than a man.

The first time I saw an olive tree, at first I thought it was a wax sculpture, dripping in slow motion into organic forms. It stood in the center of a busy traffic circle in the south of France. I was a passenger in a Peugeot, captivated as we drove around the ancient living creature that stood so humble and patient. That the tree might have stood there five hundred years before cars were even invented boggled my mind. I thought: if olives had eyes, what history they would see! And they do stand as living witnesses, known by the people that harvest and tend, honor and depend on them.

Years later, this idea came to fruition in The Life of an Olive (Heliotrope Books, 2016), a children's book I wrote and illustrated about a 2000-year-old olive tree in the Galilee. To research this book, I traveled to Israel several times and spent a week on a kibbutz harvesting olives. I also visited groves of different types, ages, and sizes. I saw olives pruned and tended, and olives gone wild in the shadow of Roman ruins near Nazareth; clinging to rocky slopes among ancient tombs painted sky blue near Tzfat; and in the white corridors of Tiberias along the Kinneret (Sea of Galilee). Olives have provided oil and fruit, mash and leaves and wood for carving, for as long as humans have dwelt here. The olive trees, in turn, are also uniquely dependent on people – for an unpruned olive cannot thrive, and does not produce abundant fruit. Thus, as olives and olive oil have helped shape human history, humans in turn have shaped the olive trees that have fed, anointed, and lit the lives of people for thousands of years.

This grove in Kaditah, northern Israel – just down the hill from where I painted Kaditah Goats – was relatively young. These trees may be a mere forty or fifty years old – barely a toddler in the lifespan of an olive. It was love at first sight when I saw these trees, as the slender youths appeared to be dancing, their receding figures in the most uncanny spacial dialogue with each other, as if the entire grove were one living sculpture.

The color, too, was striking. The shadows of the trees flipped the late afternoon light from warm to cool, so that the dry yellow grass turned to slate purple – its opposite on the color wheel. Both the colors and forms before me seemed to suggest something slightly further – an opportunity for what I call "understated exaggeration."

The painting would have to be rendered in a loose, bold style in order to pull this off – else the drama, the slight exaggeration, the nearly abstract nature of the composition wouldn't work. Painting loosely and leaving paper showing through (in this case brownish-pink, visible along the bottom of the painting), allows for movement, suggestion – and with it, that subtle quality that makes a scene more than reality. To depict a landscape is one thing; the masters who inspire me transform it into something else.

I didn't have my paints with me just then, so I snapped a photo for future reference. I work from photos only that I've taken for the purpose of painting reference. I keep these paintings in mind for months at a time until an opportunity presents itself. This one only took four months. Fumbling through my paper drawer one day, I found a piece of watercolor paper that was the right size and shape for the olive grove. I left it out on my painting table. A few hours later I spontaneously walked away from my lunch, leaving a bowl of soup unfinished while I took out my gouache paints, picked up my brush, and finished the whole painting in one sitting – about an hour. As a comparison, most of my paintings take anywhere from three to ten sittings of 1-3 hours each. Gouache is a quick medium, only a little thicker than watercolor. I don't get to use it so often, so this was a treat.

How ironic, to render something as solid and hard as an olive tree in such a loose style. The feeling is much like letting one's hair down and shaking it free. The limited palette of just half a dozen colors was also liberating – for restriction in art is paradoxically freeing. Overall, this painting was a refreshing change.

You can find Study of Olive Grove, Kaditah printed nearly at actual size in The Jewish Eye 5783/ 2023 Calendar of Art, available in my webstore and on Amazon. I contracted with a new printer this year, and I'm very pleased with the quality of reproduction.

A reminder to my local readers:

My annual art studio sale and art talk is happening next weekend!

September 24-25 from 1-4pm

at my home in Shandaken, NY

Please find sample artworks and more info here.

Hope to see you!

A good week to all –