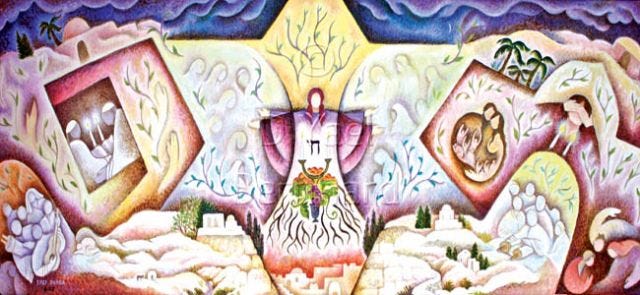

Image of the Week: The Sabbath Bride

© D. Yael Bernhard

The Sabbath has always fascinated me. Raised in a secular household, after delving into Eastern religion for twenty years, I connected with my Jewish heritage in my forties. It was Shabbat, and the concept of sacred time, that first sparked my interest.

The Hebrew word for "holy," kadesh, was first used in reference to time, not a sacred object. This concept opened the door to what I came to understand as one of the pillars of Judaism – the fourth Commandment, to remember and keep the Sabbath. Three thousand years ago this idea was far ahead of its time. In a world devoted to the worship of clay idols and appeasement of capricious deities believed to animate the forces of nature, Judaism brought forth a spiritual concept of divinity that was completely new. In this revolutionary belief system, Creation was sparked by language both human and divine, by intention embodied in the phrase "Let there be light!" As the six days of Creation were crowned by a day of holy rest, the number seven emerged as a sacred number, and the concept of pausing from labor to rejuvenate the soul was enshrined for all time.

When I learned of the Shechinah – the Sabbath bride – I was even more intrigued. This mythical figure is the manifestation of the feminine in Judaism, the earthly counterpart to God's heavenly deeds, the vessel and spirit of Shabbat. She is the healing and renewal of the soul, the in-breath that follows exertion, the silent pause in music. It is she who enfolds us in the special rest of Shabbat known as menuchah. All over the world, Jews celebrate the arrival of the Sabbath on Friday evening by singing a song to the Sabbath bride known as Lecha Dodi. The song has been put to countless melodies and reinterpreted in numerous ways, each according to the culture from which it arises.

In this painting, purple, blue and crimson are woven throughout – the colors held most sacred in the Torah. The mythical Shechinah raises her outstretched arms to the world, in which we see the hills and wadis of ancient Israel, with Jerusalem at bottom center. People are gathering, lighting Sabbath candles, singing, reading from the Torah scroll, and discussing the weekly Torah portion as the spirits of their ancestors look on. All of existence unfolds across this landscape over which the Sabbath bride extends her feminine embrace. The Jewish people find refuge and renewal in Shabbat each week – and in the divine presence of the Shechinah, who no one has ever seen, and who no two people imagine the same way. This is one way I envision her.

The Sabbath Bride is the image for October in my new calendar, The Jewish Eye 5784/2024 Calendar of Art. The calendar is available in my webstore ($20 with shipping included) or on Amazon ($16.95).

You can view the entire calendar here.

The Sabbath Bride is a large painting, acrylic on canvas, measuring 5 feet wide. It was designed to hang over a doorway in a synagogue, which it did for many years until the beginning of the pandemic. The painting is for sale; please inquire if you're interested.

Starting next week I will leave the The Jewish Eye behind and start writing about other subjects again, as every painting in the calendar but one has been covered in this newsletter over the past few months. If you want to read any of those posts, the archive is here.

To all my Jewish readers, Shana tova u'metukah – a good and sweet new year!

D Yael Bernhard

children's books • fine art • illustration