Maggid (The Telling)

Maggid, acrylic & oil on canvas, © D. Yael Bernhard 2024

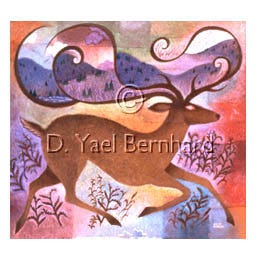

Here is a fanciful depiction of perhaps the oldest and most beloved Jewish holiday tradition: the Passover seder. “Seder” means “order,” and consists of a sequence of blessings, readings, songs, the tasting of symbolic foods, a festive meal – and my favorite part, the telling of the story of Exodus – the part of the seder known as Maggid.

The Hebrew word maggid or magid (מַגִּיד) is difficult to translate. It roughly means “storyteller” – but not just any storyteller, like a bard. A maggid serves God, and transmits spiritual energy through the telling of sacred literature. A skilled maggid communicates much more than the content of the narrative. The word implies both the telling and the teller rolled into one, just as all Jews are rolled into the timeless story of liberation from enslavement. It is customary to tell the tale in present tense, as if we are there with Moses, escaping from Egypt, witnessing the parting of the Red Sea, crossing on foot into freedom and responsibility. Narrative is the nourishment on this table, as the story of Exodus is considered to be the “meat and potatoes” of the seder. Passed down from generation to generation, this home-based tradition has survived over thirty centuries, through times of persecution and upheaval, immigration and even secularization. In Israel and America alike, even secular Jews participate in the seder, which evolves with the times, ever changing according to the minhagim (local customs) of families and communities.

Years ago I was invited to write a review for a Jewish magazine, of a book about medieval illuminated manuscripts, titled “Skies of Parchment, Seas of Ink.” In return for writing the review, I was given a copy of this elegant hardcover treasury. I did not have to read the entire volume from cover to cover in order to write the review, but I did. The experience had a profound effect on my art. Layer after layer of meaning peeled back from the stylized figures and decorative designs reproduced in the book. The artists of bygone centuries who created these works seemed to be forging a visual architecture. Some of the manuscripts – including Passover haggadot (seder guidebooks) – showed figures with animal heads, to avoid depicting human attributes, forbidden in those times in strict adherence to the second Commandment, not to create any form of idol. Even a two-dimensional drawing of a person could be mistaken for an image of God, and wrongly worshipped. The resulting animal-headed creatures populated the pages of these impressive hand-painted tomes that were passed down from generation to generation as family heirlooms. Unlike a house or a synagogue, a book was easily hidden or transported in times of persecution or migration. Hidden meanings were embedded in the images, the text, and even the decoration of letters – including family records, political commentary, codes for safe passage, and more.

Since we are meant to relive Passover each year as if we are alive in the past, I felt justified in combining the many historical elements of the holiday into a contemporary image. My painting incorporates animals of the Northeast forest where I live – animals acting like humans, hungry for knowledge, gathered around a seder table with the most pivotal scenes of Exodus painted on the plates, and a tablecloth bordered with Jerusalem. The Hebrew word at the bottom says “maggid” in a typical medieval style, with the letters formed into mythical creatures. The human imagination was bursting forth in those times, budding into new forms of visual expression that may seem unremarkable today, but were groundbreaking then, laying the foundation for the rise of humanism and the Renaissance that followed.

Today animal-headed figures seem childish, as we have all grown up with anthropomorphized characters in our favorite picture books, from Richard Scarry to Maurice Sendack and far beyond. These charming figures had a different purpose centuries ago, but continue to pique our imagination. For in many ways, animals do seem human. Watching a couple of seagulls at the ocean a few days ago, I couldn’t help noticing how readily my mind interpreted their behavior as human. Such is human perception, and human pondering.

Maggid is the image for next April, when Passover takes place, in The Jewish Eye 5785/2025 Calendar of Art. Rosh Hashanah is just three weeks away! The calendar makes a great gift for the New Year. The Jewish Eye is available in my webstore ($20.95 including shipping), on Amazon ($18), and locally at the Tender Land giftshop ($18) in Phoenicia, NY. All the images may be viewed in my webstore.

The original painting of Maggid is also for sale. Please inquire for details if you’re interested.

If you’re local, you’re invited to my art sale on September 28, 29, and 30th – you should be getting a separate email announcement about that; if not, please respond directly to this post for more information.

A good week to all!

D. Yael Bernhard

https://dyaelbernhard.com

Have you seen my other Substack, The Art of Health? In addition to being a visual artist, I’m also a certified integrative health & nutrition coach with a lifelong passion for natural food cooking and herbal medicine. Now in its second year, this illustrated newsletter explores cutting-edge concepts of nutrition. I strive to make relevant information clear and accessible, and to anchor essential health concepts in unique images. Check it out, and if you like it, please subscribe and help spread the word. Your support keeps my work going!